Transforming/reinventing public education in America is well within the realm of possibility because it is a relatively simple human engineering challenge. The obstacles to its realization exist not in the architecture or mechanics of a solution rather in the politics of change. Those obstacles begin with how difficult it is for people to step outside their paradigms and envision a different reality. Being able to envision a new reality is important to all human beings but is imperative for educators if we are to insure equality in education.

The danger we all face when confronted with a long history of disappointing outcomes is succumbing to resignation that we are powerless to alter those outcomes. It is so easy to become inured to the human consequences.

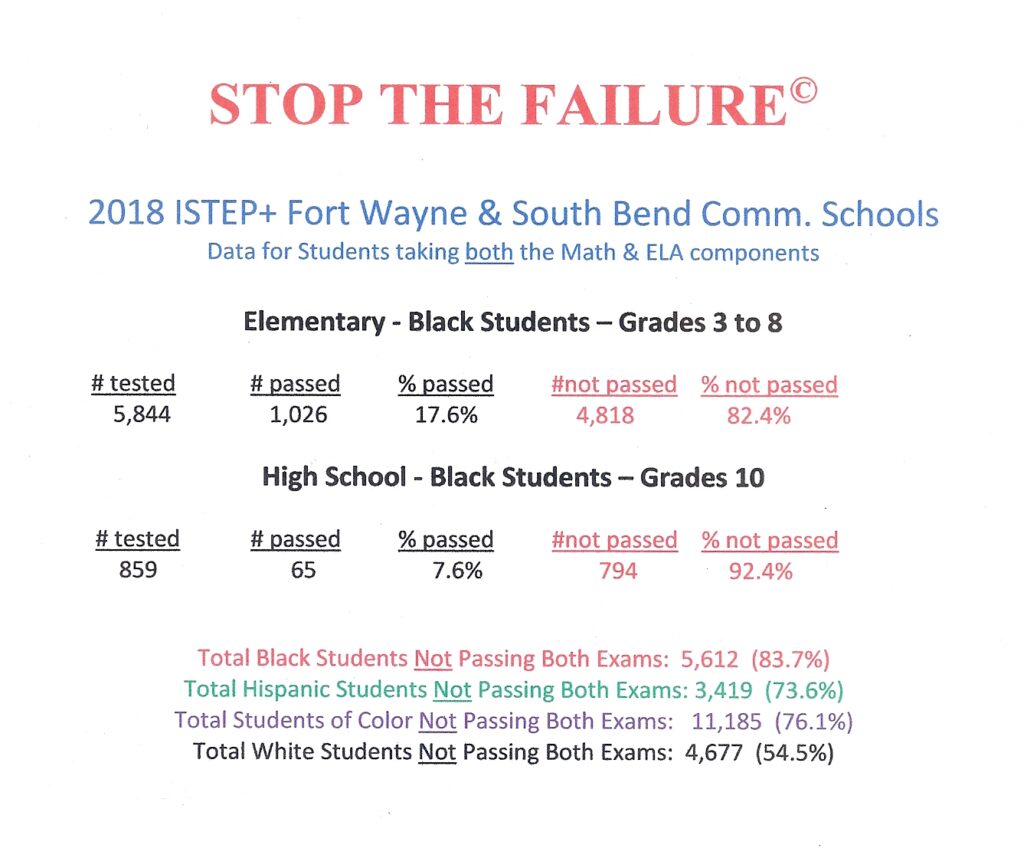

In public education, disappointing outcomes have been a fact of life for generations and the consequences have had an adverse impact on virtually all aspects of American society. Teachers entering the profession almost always believe that all kids can learn but, over time, they are confronted with the reality that so very many of them do not. Some educators succumb to the proposition that there are children who cannot learn.

That so many of these students are poor, black, and other minorities makes it inevitable that some men and women—not a majority, we believe—will draw unfortunate conclusions. Educators must be challenged to reject stereotyping or profiling by racial, ethnic, or any other categorization and conclude, instead, that the problem is not that these kids all look alike, rather that they experience similar disadvantages.

This tradition of unacceptable outcomes will not be altered until educators take a paradigm leap and imagine a new reality outside the boundaries of conventional thinking. Envisioning an alternate reality does not guarantee a solution, however. Even when we discover a transformational solution, we are still faced with one of greatest challenges facing organizations; we must overcome the paralysis of inertia.

What teachers, principals, and other administrators must do is simple. They must acknowledge that what they are asked to do in their schools and classrooms is not working for many students, especially the disadvantaged. They must be encouraged to forget about what the critics say; forget about the corporate reformers and the politicians who have been influenced by them; and, forget about test scores.

The only thing that matters to teachers is what they see in their classrooms. Not all teachers can see the pattern from their classroom, however, nor can all principals. Those educators blessed to work in high performing schools must not turn a blind eye to the challenges faced by so many of their colleagues. They must remind themselves, often, that “if not for the grace of God, that could be me.” They must stand shoulder to shoulder with their colleagues in our most challenging schools and districts.

Superintendents have a special responsibility to provide positive leadership and in districts populated by struggling schools and failing students, superintendents must be strong enough to share the truth of what they witness. Their responsibility includes their students, the men and women who staff their schools, and the communities they have been chosen to serve. It serves none of these interests to act as if everything is okay.

It may be unreasonable to expect all top administrators to break from tradition, but they must be relentless in challenging the assumptions of conventional wisdom. When these leaders see a long pattern of academic distress, they must feel compelled to act because if they do not, who can?

It is not my desire to shower these good men and women with blame, but I do challenge them to accept responsibility. Blame and responsibility are two entirely different things. There is an essential principle of positive leadership that suggests “it is only when we begin to accept responsibility for the disappointing outcomes that plague us that we begin to acquire the power to change them.”

It has long been my belief that the top executives of any organization must be positive leaders with a passionate commitment to their mission. I have observed far too many leaders in education, whether superintendents or principals, who appear to be administrators more than powerful, positive leaders. Because most were hired and are evaluated based on their administrative experience and skills, we should not be surprised. Those graduate programs for school administrators that do not place great emphasis on leaderships skills must be challenged to rethink their mission.

It is my assertion that the absence of dynamic, positive leadership in school districts throughout the U.S. has given rise to a groundswell of dissatisfaction that, in turn, has opened the door for education reformers. These reformers—also good men and women—are only striving to fill a void of leadership. They see inaction from the leaders of public schools in the face of decades of unacceptable outcomes. Those outcomes are the millions of young people leaving school without the academic skills necessary to be full partners in the American enterprise.

What is unfortunate is that the solutions these education reformers and their political supporters offer have proven to be no more effective than the public schools they are striving to supplant. And, why should we be surprised when all they do is change buildings, call it a charter school, and ask teachers to do the same job they would be asked to do in public schools. They rely on the same obsolete education process and it is inevitable that they will get the same results.

This flawed education process impacts every child, adversely. To disadvantaged students, those impacts are often devastating.

Once again, I ask the reader to consider an alternate approach; a new model designed to focus on relationships and giving every child as much time as they need to learn every lesson, at their own best speed. Please check out The Hawkins Model© not seeking reasons why it won’t work rather striving to imagine what it would be like to teach in such an environment.

The ultimate measure of the success of our schools is not graduation rates, or the percentage of students going off to college. Education must be measured by each student’s ability to utilize, in the real world, that which he or she has learned; regardless of the directions they have chosen for their lives. Education must be evaluated on the quality of choices available to its young men and women.

Whether you are a teacher, principal, or superintendent, how does one explain that all your dedication, best efforts, and innovation over the last half century have produced so little in the way of meaningful improvements in the outcomes of disadvantaged students?

Blaming outside forces is unacceptable. If the pathway to our destination is obstructed, do we give up or do we seek an alternate route? If we succeed in treating the illnesses and injuries of some patients does this let us off the hook in dealing with people whose illnesses and injuries are both more serious, and more challenging? “They all count, or no one counts.”

It serves no purpose to beat the superintendents of our nation’s public school districts about the head and shoulders, but we have a responsibility to hold them accountable.

If teachers would rally together and utilize the collective power of their unions and associations to challenge conventional wisdom, they would gain support and become a revolution. The same is true of administrators and their associations. If teachers and administrators would link arms, they would become an irresistible force, not for incremental improvements, but for transformational change.

Is there any doubt in the reader’s mind that if teachers and administrators were united behind a positive new idea that would assure the quality of education of every one of our children, that their communities would rally to the cause?

Educators, you truly do have the power to alter the reality that is public education for every child in America.